This reflection was submitted as a cross-curricular reflexive write for Foundations of Education – a Bachelor of Education course at UNBC. I wanted to take this space to reflect on a concept that’s been present in my thoughts since recently finishing the book Potlatch as Pedagogy by Sarah Florence Davidson in collaboration with her father Robert Davidson (2019). On page 71 Sarah Florence Davidson reflects,

In his teachings, my father has always emphasized the importance of making a contribution; he does this through hosting feasts and potlatches, mentoring emerging artists, and sharing the knowledge that he has gained through his experiences… Though these examples of contribution differ from fishing for halibut with his tsinii, the significance of making a contribution remains the same.

She then goes on to reflect that there are two aspects to this teaching. The first being that when learning is for the purposes of contribution, it can feel more pressing. As an example she offers that if your family relies on fish for food, you’re likely to be a more motivated learner of the skills and lessons needed to fish well. The second involves the cultural imperative of contribution, on the subject of which she reflects, “My father learned from the Elders for the purpose of sharing his knowledge, just as I pursued my education because I wanted to be able to contribute to my community through what I learned at school.” (|Davidson, S.A., 2019)

In this book, Sarah Florence Davidson is in conversation with her father, a prolific Haida artist and the first person to carve and raise a pole in Haida Gwaii following the end of the Potlatch ban. He reflects many times throughout the book that when he began working on the poll, he had no idea of the scale and significance the project would become. As elders gathered, spoke the Haida language, and reassembled protocols from their collective memories and oral histories, the poll became part of a much bigger cultural re-knowing. The process unearthed songs, dances, ceremonies, and potlatch protocols that had been decimated by the Indian act and the Potlatch ban over the previous hundred years. In contributing this poll to his community, Robert Davidson learned stories, histories, and cultural teachings that would have likely been lost in a short few years as those elders began to pass on.

I have a personal interest in the concept of mutual aid that stems from my career in social services, trying to access supports and communities for my clients outside of the non-profit industrial complex and the violence of the carceral justice system and government systems like MCFD and the ministry for social development and poverty reduction. The concept, which dates back in name to anarchist philosophers of the late 19th century, but which has been articulated in the ways that interest me by queer, trans, and bipoc community organisers of the late 20th and early 21st century, emphasizes a belief in solidarity over charity. An understanding that none of our needs are truly adequately met by the violent and oppressive systems under which we are governed, but that we can meet each other’s needs, communally, as they arise (Spade, 2020).

Within a cross curricular, educational context, these ideas of “Learning Occurs Through Contribution,” (Davidson & Davidson, 2019) and “Solidarity not Charity,” (Spade, 2020) feel in keeping with the teachings of abolitionist philosophy as articulated within the teaching space by Bettina Love in her 2019 book We Want to do More Than Survive. By that I mean, she speaks to the need for genuine civics education wherein students are presented with examples of political organising and resistance to injustice so that they have a framework for true civic engagement beyond the obligations of voting and taxes. It is my belief that learning through contribution is a potential overarching philosophy for developing knowledge, skills, and sense of communal responsibility in students that is rooted in a strong sense of mutual aid and an understanding of communal love and service as a historically rooted means of resistance against violent systems that oppose the knowledge that each child, and each person, has inherent value.

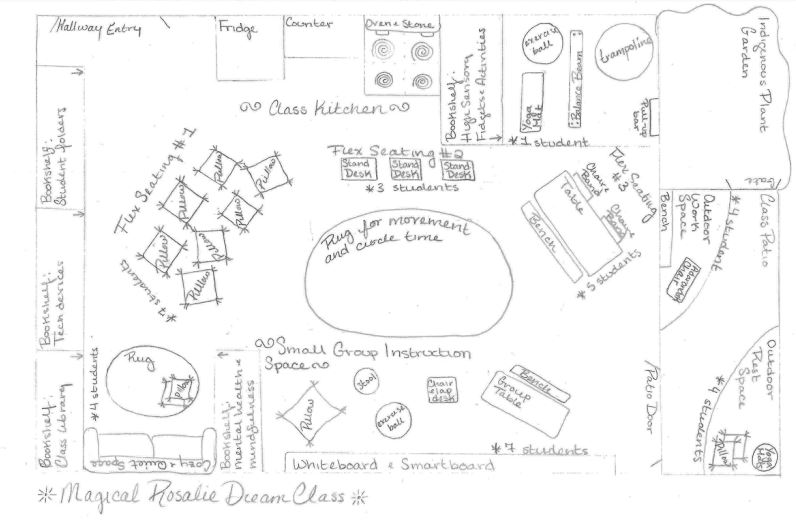

In practise, I imagine this to look like teachers taking the time to build authentic relationships with the families of their students, as well as community organisers, elders, knowledge holders, sports organisations, leaders of arts initiatives, youth center staff, community center staff, and any other “stakeholders” in the community where teachers live and work. In building these relationships, I expect that teachers will begin to see and know the needs for contribution that a community has. Then, it is my hope that teachers would work with students to understand how they might build up their communities via contribution and make a plan to embed the idea of community based mutual aid in their learning.

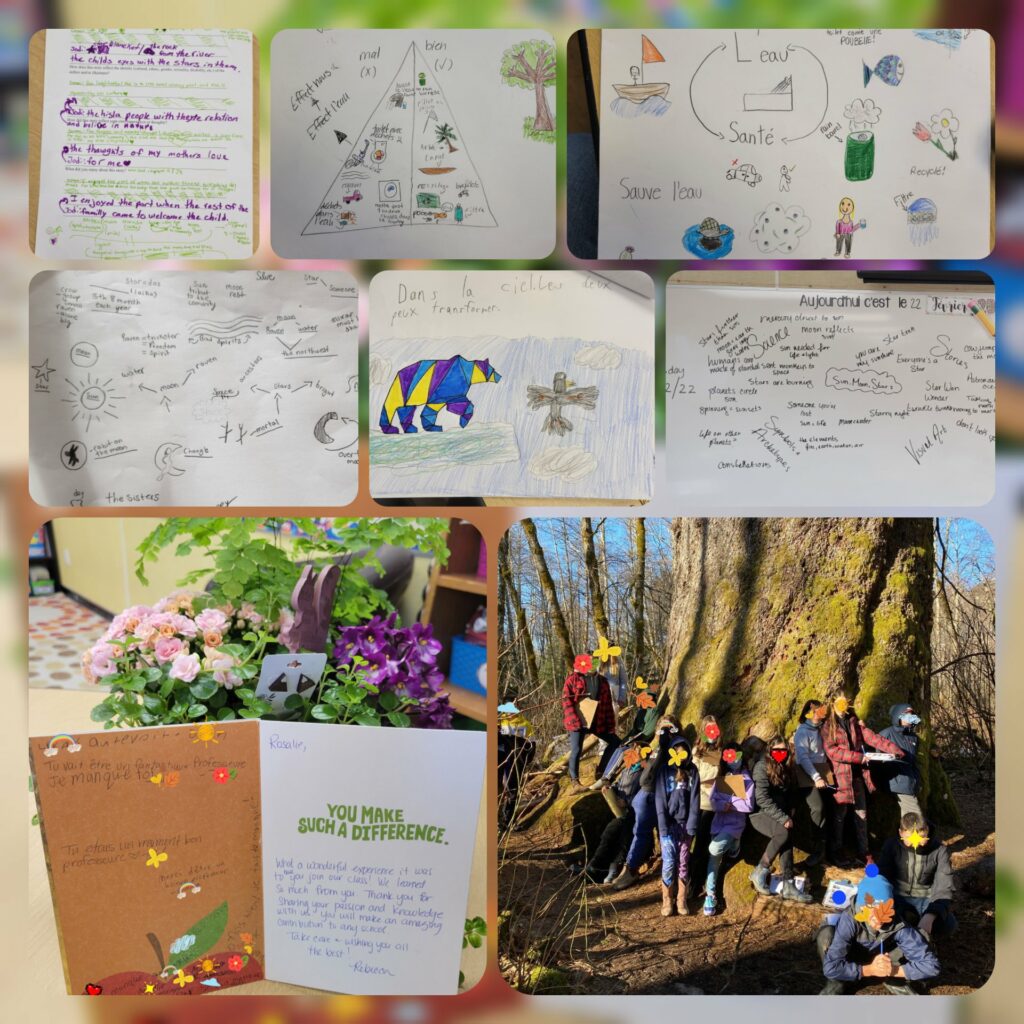

An example of this in many regions of BC, would be the efforts to revitalise Indigenous plant foods and remove invasive species. In doing this type of community based contributive work, students have potential to engage with cross curricular learning in the areas of First Peoples Knowledge (science and social studies), plant ecology and ethnobotany (again, science and social studies), benefits of outdoor physical activity for holistic mental, physical, social, and spiritual health (physical education), thinking about and telling stories (language arts), and potentially with the right community collaboration, exposure to local Indigenous languages in the context of plant knowledge (languages, and social studies). In creating a model of learning founded in communal contribution, students become active participants in their learning, and have a reciprocal relationship with their teachers (the land, knowledge holders, fellow students, and their formal classroom teacher). This fits within not just standard curriculum requirements as detailed, but also strongly supports several of the First Peoples Principles of Learning.

Ultimately, this approach has potential to meet curriculum outcomes, First Peoples Principles of Learning, and the BC Teachers Standards (particularly 1, 4, 5, 6, 8 and 9). It incorporates components of Ontological philosophies including realism, pragmatism, and existentialism, and normative philosophies including essentialism, perennialism, progressivism, and social reconstructionism. It can be used as a framework for inclusion based on true authentic connection and an understanding of differences as part of a whole community rather than deficits to a person’s function within capitalist and colonial systems of power. In learning which occurs via contribution, students integrate knowledge and develop a sense of mattering (Love, 2019) that leads to an intentional understanding of civic engagement, communal uplift, and knowledge as an integrated practice that is grounded in authentic relationships to the self, one’s community, and the land on which we learn.