To view full lesson, please click on the image below

“Educators value the success of all students. Educators care for students and act in their best interests.” – Professional Standards for BC Educators, 1.

This standard has been on my mind as I begin my work in schools and continue on my practicum journey. I am interested in the word “value” as it is used in this phrase. It is my observation that what lacks in many cases, especially in small northern communities, is not necessarily a valuing of success but rather a belief in the possibility of it. Teachers largely seem to care for and value the students in front of them, however there is a prevalent pedagogy of low expectations, particularly when it comes to disabled students and Indigenous students.

Despite increasing traction for movements focused on meaningful inclusion, disabled students are often still othered in a way that not only devalues their success, but seems to more broadly reveal a general dehumanization. Many disabled students are not centered in their own learning, their goals and dreams are not considered (and at times it is not even acknowledged that they may have goals and dreams for themselves), and their success is secondary to the ease and success of abled and neurotypical students. This results in disabled and neurodivergent students being left to do work away from their peers, below their skill levels, and with inadequate support to facilitate growth. I should note that while individual teachers have a responsibility to disrupt this cycle, it is often a part of a larger structural void where teachers and EAs are insufficiently supported (and staffed) to facilitate the success of all students, and disabled and neurodivergent students are frequently one of the first sets of learners to be left to fail.

Indigenous students experience a similar othering on a systemic level. It has been my observation that in many schools Indigenous students are not offered a presumption of competency. One area in which this is particularly evident, is the allowance of high rates of functional illiteracy despite strong evidence that the vast majority of students are capable of learning to read. We know that low literacy rates correlate to higher incidences of incarceration, homelessness, food insecurity, and experiences of violence, yet it is seen as a natural or acceptable condition for Indigenous students. If we were to presume competency, then the onus would be on us as teachers to be effective in our teaching of reading (and on the system to provide teachers adequate resources and education to that effect). Instead, students fall through what I’d sooner call an earthquake than a crack.

I do not mean to imply that teachers do not care about their students. I believe that on an individual level the vast majority of teachers care deeply about each young person in front of them. What I believe is lacking, is a broad understanding of the deep systems of oppression and violence that follow students through their education and color the ways we interact with students despite any care we have for them. I believe that as teachers we value the idea of success for our students, but especially when it comes to students who have been marginalized, and in this region more specifically disabled and Indigenous students, teachers must force themselves to not just value success, but to believe it is possible.

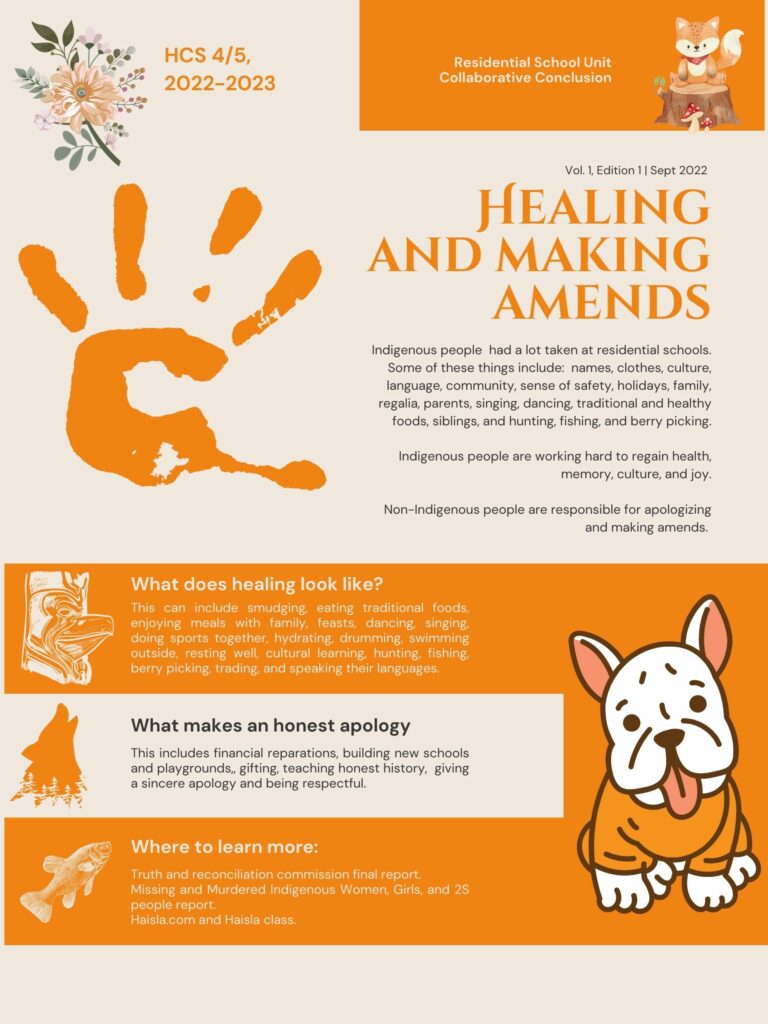

The above poster was the collaborative summative evaluation generated entirely by my grade 4/5 students at the Haisla Community School. Students spent a month learning about residential schools, and the colonial and genocidal contexts in which they were created. Students discussed the ways these systems continue today, and how Indigenous communities are actively undoing the harms that were done to them. It is worth noting that almost all of my students are Indigenous and living on or near their traditional territories.

This unit was, for me, the product of significant reflection on the grade 4 curriculum, on how to appropriately teach in the lead up to orange shirt day, and on standard 9 of the Standards for Educators. I knew it was my responsibility to teach this history honestly and I was also cognizant of my positioning as a white woman standing in front of students who largely have personal intergenerational trauma as a result of the subject matter being taught.

I am particular struck by one sentence in Standard 9, which reads, “Educators contribute towards truth, reconciliation, and healing.” I felt equipped to teach the truth, and I’m not quite sure how I personally understand the word reconciliation, but contributing towards healing felt like an enormous endeavor. What I could not have anticipated was the way my students undertook that component themselves.

In their reflections on the jobs of Indigenous peoples in the word of undoing the harms of residential schools I was particularly struck that they chose to write about reclaiming joy. As they expanded on what healing looks like, they spoke of family, feasting, dancing, but also resting and playing. My students showed me in this unit that when asked, Indigenous people, even kids as young as nine and ten years old, know what is needed to heal – if they can be given a safe and supportive place to undertake that work.

This is a post that reflects something I think about all the time in my classroom. I have been grateful to learn about this in disabled community, from disability justice activists, and from youth I’ve worked alongside. Everyone has needs. Some needs are met by dominant society (I can’t just jump through my front door, I need steps. I can’t read in the dark, I need lamps. Etc.] Disabled students often have needs that aren’t met by dominant society. This is because dominant society was built for and by primarily able bodied, neurotypical people due to the systemic exclusion and institutionalization of disabled and neurodivergent people and the prioritization of economic growth over community care.

We are not obligated to accept that as teachers. In my classroom all students have access to noise canceling headphones and earplugs. The tables are set up for easy navigation with mobility aids. Students can choose what type of seat they need. Eye contact isn’t assumed to be synonymous with attention. Verbal communication doesn’t take priority over AAC or written communication. These are small ways I disrupt the idea that some needs are special or additional.

All students have needs, and because I see teaching as community driven labour, I believe the needs of the entire community deserve to be met. Meeting these needs isn’t additional or special. It is essential.

[ID: a graphic of three people holding flags. The two people on the outside stand, the person in the middle is in a manual wheelchair. Above the picture in large letters it reads All Students Have Needs. Below that in smaller letters it reads Some needs are just already being met. Below the picture reads in even smaller letters Disabled students do not have “special” or “additional” needs]

Fireweed is abundant in the northwest, it is a Native Plant, the polinators love it, and it makes a delicious jelly. I made this recipe with my family, and then with students, and it was a great opportunity to talk about plants, the connections between plants and their environment, fractions, and some simple chemistry. Here is the recipe and a quick video of my family making it. Included in the video is fireweed tea or “Ivan Chai,” which I will hopefully have time to share about in the future.

Materials

Instructions

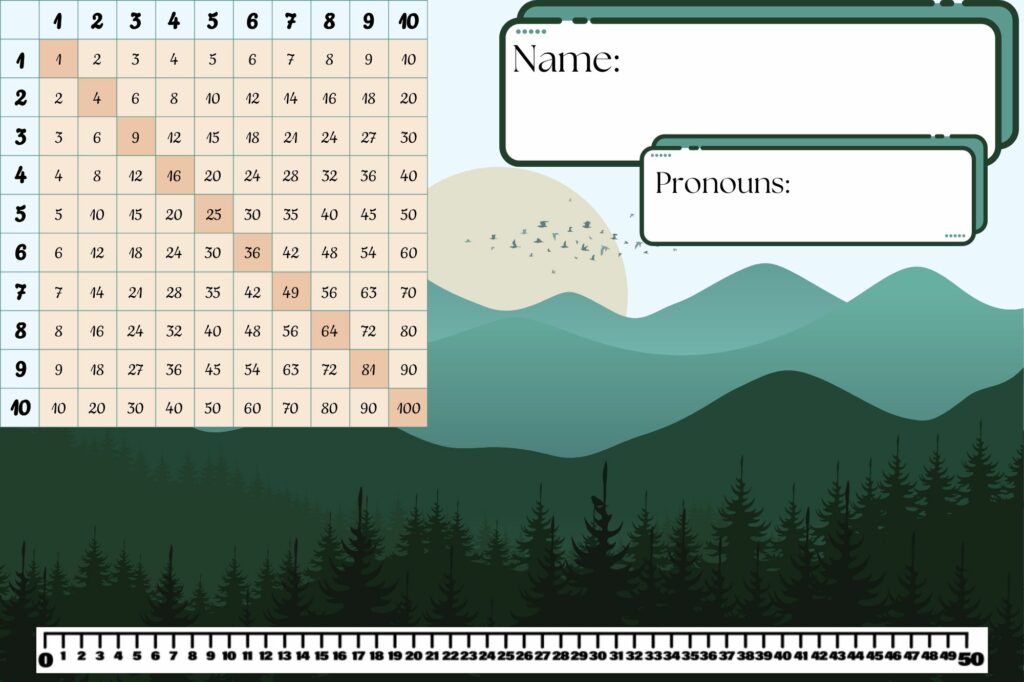

This year I will be continuing a practice of flexible seating implemented by my predecessor. On my practicum, I liked that students could use number lines and multiplication tables kept at their desks, however with flexible seating I knew this might not work so well. My predecessor had these items in bins for the students, but the students frequently lost them. I created a laminated placemat to solve this issue, and it also has a space for them to add their name and pronouns so that in the first few days of school I am more able to keep track of who is sitting where and how they’d like me to refer to them without the ease a seating chart can provide.

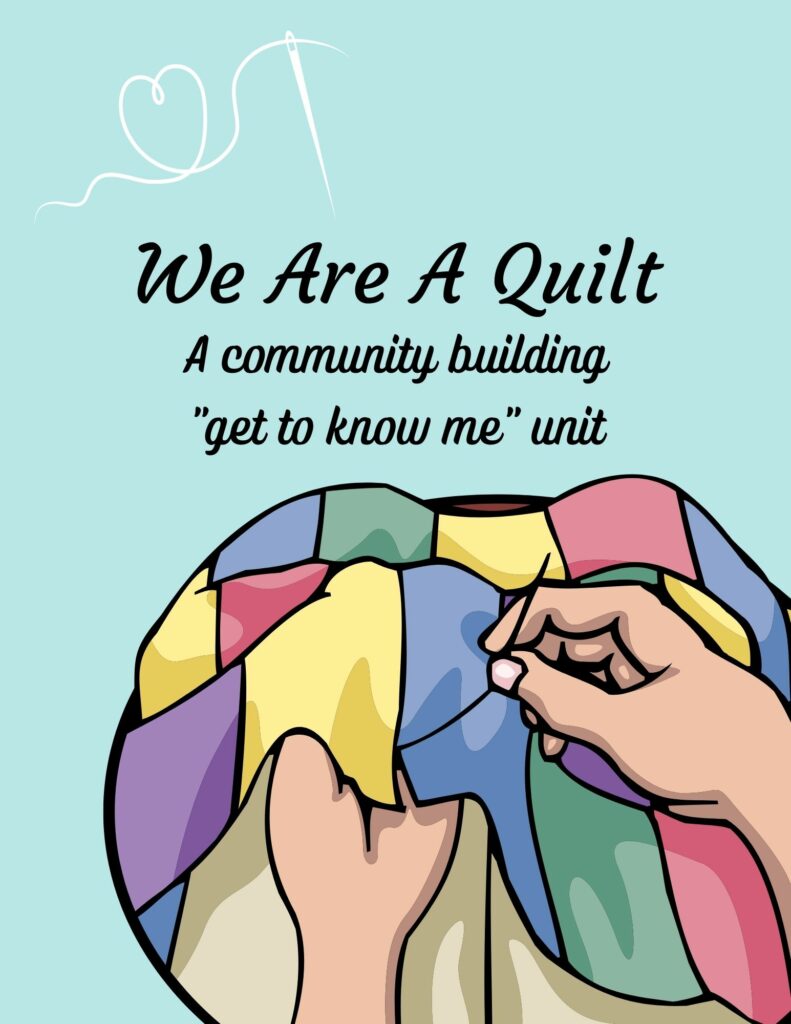

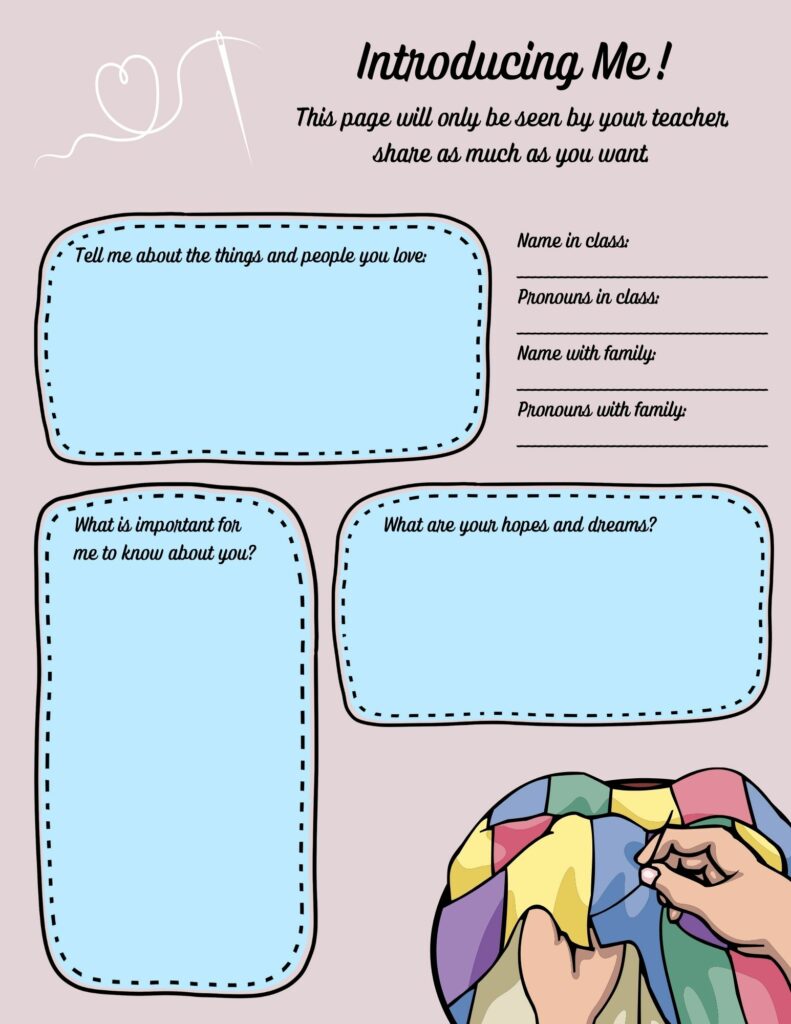

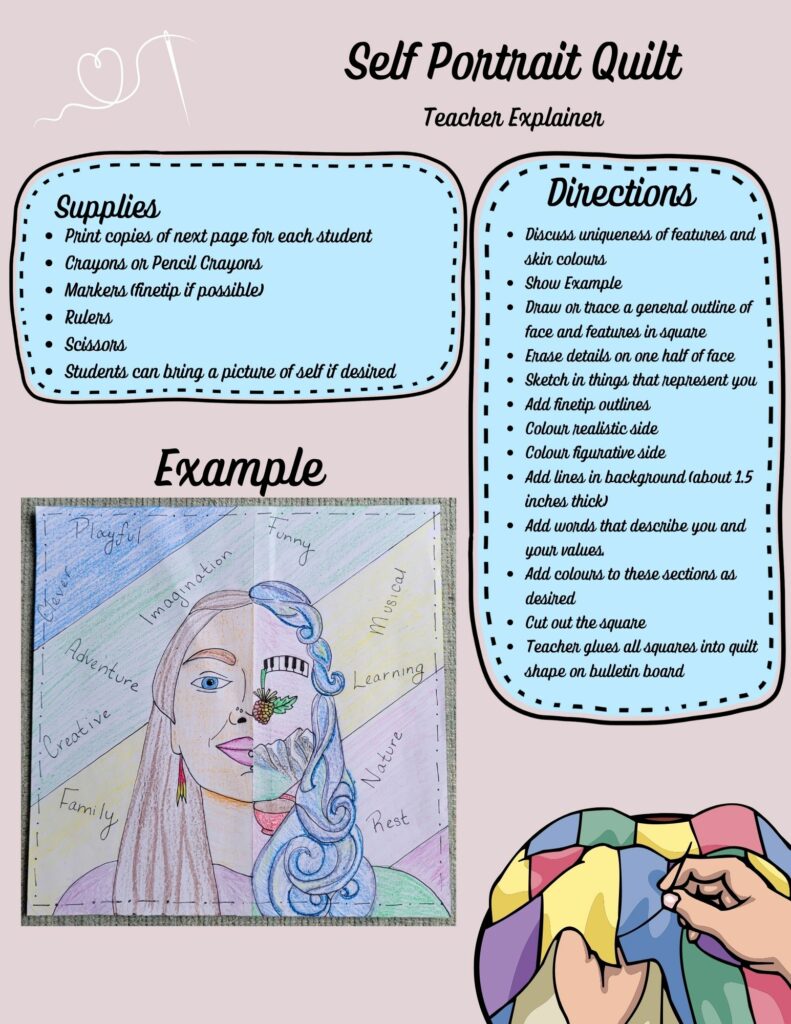

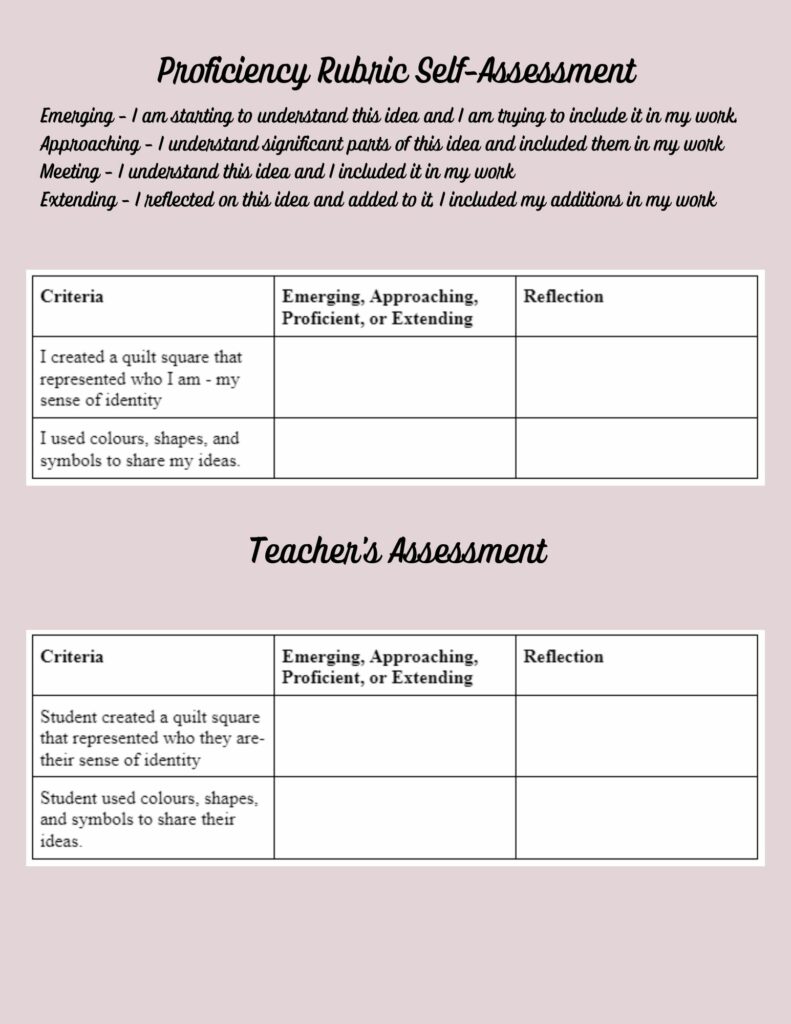

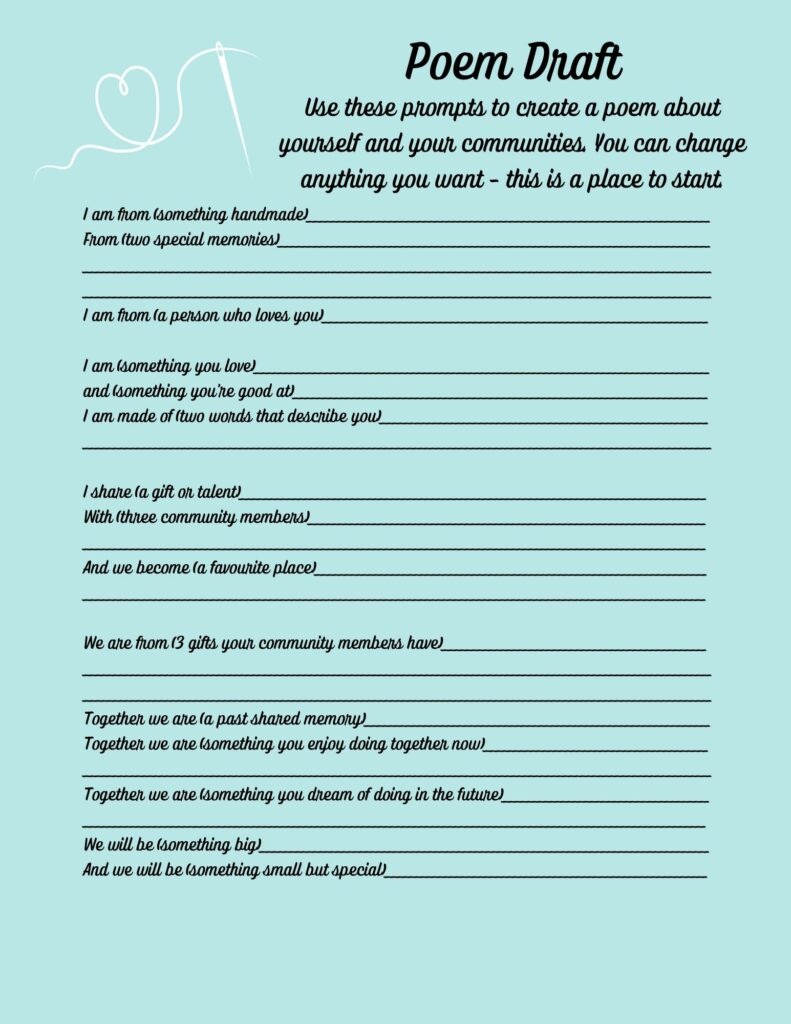

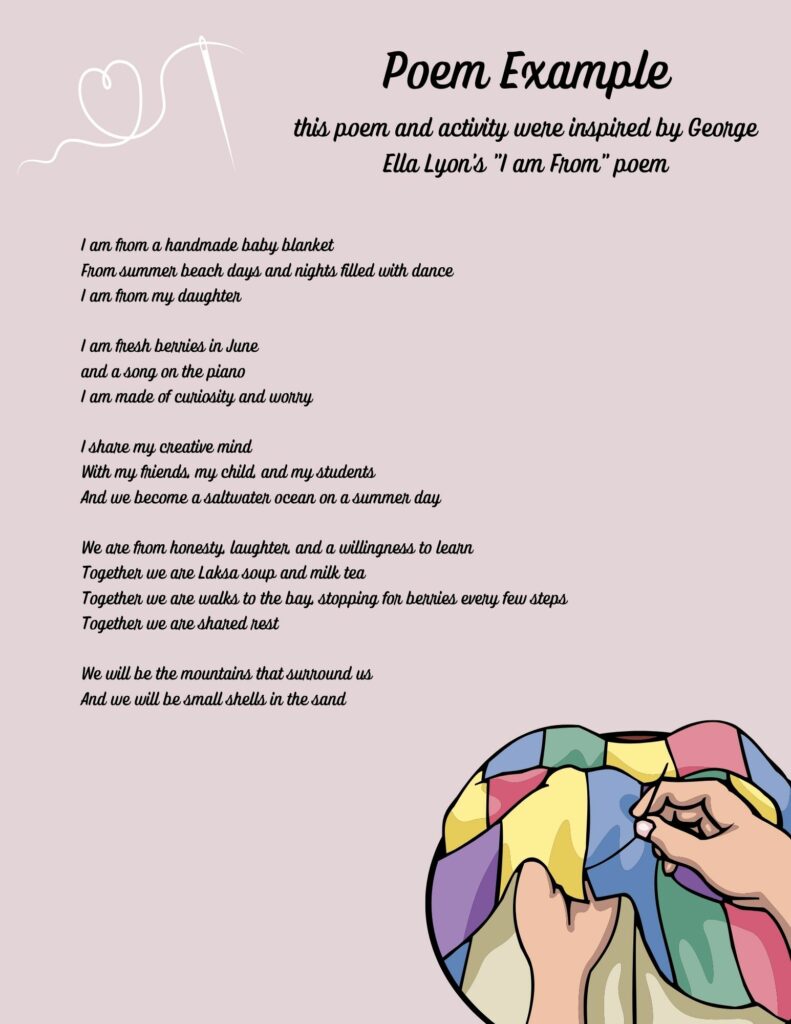

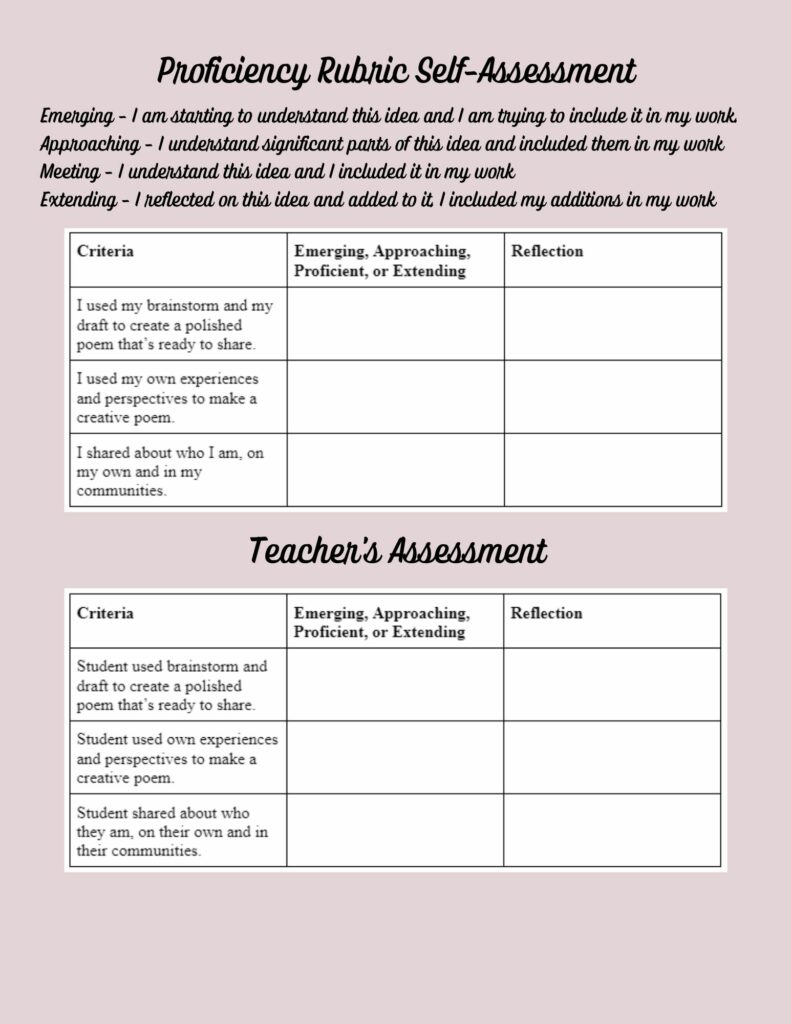

The following unit is how I intend to start my year with my grade 4/5 students. It is an opportunity for them to share with me about who they are, their interests, their families, and set the tone for how they want me to see them. It is also a quick way for me to get a sample of their writing, get a sense of how comfortable they are with planning and revising, and identify students with creative strengths that can be nurtured throughout the year.

You may also click on the first photo to be linked to a copy of this unit.

© 2025 Meet Ms Rosalie

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑