Justice-Doing and Abolitionist Frameworks

Love, B. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

This book addresses the inequities of the American education system through an abolitionist lens. It problematizes the status quo in education, arguing it needs to be dismantled and rebuilt from the ground up, not reformed. Love argues that educational inequities for racialised students cannot be fixed if teachers are not aware of the underlying systems of racism and colonialism that impact them. She touches on the intersectional ways education can be an oppressive force for marginalized students who are not just racialised but also queer, trans, disabled, poor, or otherwise impacted by inequities in society. The book describes a variety of strategies for abolitionist teaching – this is not presented as a pedagogy but as many different ways educators may engage in pursuing educational freedom. At the center is the concept of “mattering” in the solution to educational inequity – students need to have a sense of “mattering” to succeed. Ultimately, the author describes the importance of loving our students and knowing their collective histories so we can best serve them as educators.

Reynolds, V (2012). An Ethical Stance for Justice Doing in Community Work and Therapy Journal of Systemic Therapies Vol. 31 (4). 18-33

Reynolds writes from a place of deliberate imperfection about the action of “justice-doing” in a world that is largely failing to provide social or other forms of justice to oppressed and colonised peoples. She explores the benefits of what we traditionally considered to be therapy or wellness, things like counselling and medication, and acknowledges their imperfect benefits, but suggests that what we really wish for is a world in which we can offer justice. She speaks to the concept of being in solidarity not as theory but as a way of rooting our practices, using the Zapatista phrase “we are you.” While emphasizing the value of solidarity she also engages with the realities of power dynamics and the imperfections of allyship. She emphasizes the way we co-create both spaces of justice-doing, and the practices themselves. In these ways, she emphasizes the ways social and emotional wellness require that we pursue a just world.

Thom, K. C. (2019). I hope we choose Love: A trans girl’s notes from the end of the world. Arsenal Pulp Press.

This book is written in a variety of formats including poetry, memoire, and essay. While it is not specific to the school context, it offers a politically and personally grounded perspective on community, inclusion, and politics of disposability. I read this book early on in my teaching career, and have found it to be continuously helpful in understanding the many ways students are impacted not just by identity, but the challenges and blessings of being part of a “community.” I go back to Thom’s nuanced views of the world often, and find their praxis of choosing love to be central to how I show up to support the social and emotional wellbeing of my students.

Indigenous Language Revitalisation and Social-Emotional Outcomes

McIvor, O. (2013). Protective effects of language learning, use and culture on the health and well-being of Indigenous people in Canada. Proceedings of the 17th FEL Conference. FEL XVII: Endangered Languages Beyond Boundaries: Community Connections, Collaborative Approaches and Cross-Disciplinary Research, Ottawa, ON (pp. 123-131). Foundation for Endangered Languages in association with Carleton University.

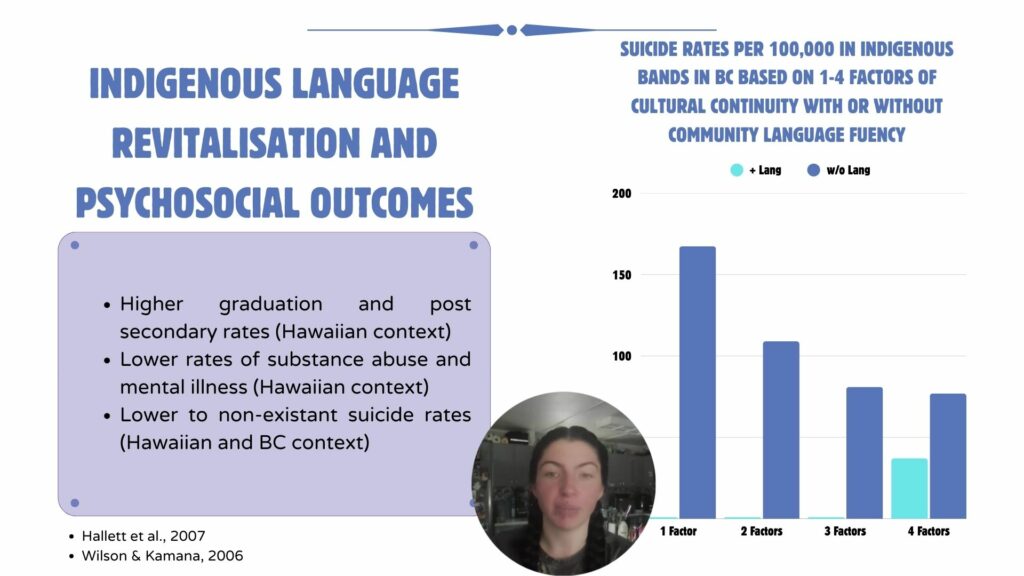

Dr. Onowa McIvor’s work on Indigenous language revitalisation has been foundational to my understanding of language revitalisation not just as a linguistic act, or even a political act, but as a movement that is essential to the health and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples. In particular, I chose this article to include as it outlines the impacts of developing fluency on the health outcomes of Indigenous people, finding that those who feel meaningfully connected to their language and culture, and reach a conversational level of fluency, are at lower risk of death by suicide, not just as compared to Indigenous peers, but as compared to all peoples in cka canada. In beginning to understand language as a non-metaphorical act of decolonisation with the potential to reverse the health (including mental health) impacts of colonisation, my entire understanding of the systemic nature of SEL shifted.

Whalen DH, Lewis ME, Gillson S, McBeath B, Alexander B, Nyhan K. Health effects of Indigenous language use and revitalization: a realist review. Int J Equity Health. 2022 Nov 28;21(1):169. doi: 10.1186/s12939-022-01782-6. PMID: 36437457; PMCID: PMC9703682.

This article outlines similar outcomes to that of McIvor’s 2013 research. While the outcomes vary slightly more, and the context is less localized to BC, this paper is still helpful in understanding the ways in which language learning are essentially connected to the physical and mental health of Indigenous students. In particular, when considering 5 factors of cultural access and involvement, as well as conversational or higher language fluency, Indigenous youth have fewer health disparities (including higher life expectancy), higher literacy rates, and nearly 0 risk of suicide attempt.

Wilson, W. H. (2006). Näwahï Hawaiian Laboratory School. Journal of American Indian Education, 45(2), 42–44.

Building further on this, the case example of theNäwahï Hawaiian Laboratory School is particularly relevant. While Native Hawaiian students in Hawaii have generally high rates of substance use difficulties and mental health challenges including suicide and suicidal behaviours, students who graduate from Nawahi experience the opposite. A full-immersion program based out of a lab school of the University of Hawaii at Hilo, their program involves the entire family in a culturally rich language immersion setting. The outcomes are awe inspiring, as their students go on to graduate and attend post-secondary at double or more the rate of their English-medium education peers. Equally as important, they have not had any deaths by suicide, and student self-rating of wellness is consistently high. This program, for me, solidifies the belief that in order to support Indigenous students to achieve genuine wellbeing, we must support access to language fluency programs.

Indigenous and Decolonial Perspectives and Frameworks

Nunavut Department of Education (2007). Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Education Framework. Nunavut Department of Education, Curriculum and School Services Division.

This report comes from the education department in Nunavut, and explores an Inuit epistemological approach to the education system. It is an excellent example of educational sovereignty and the ways in which cultural frameworks can be used to understand and promote wellbeing of students and the broader school community. I was especially struck by the idea of values as being at the core of behaviours. When behaviours are not as we hope in our students, we must find ways to support them in building a value in that area. This was a new concept to me, and one I will consider going forward in my work.

Davidson, S. F., & Davidson, R. (2019). Potlatch as pedagogy: Learning through ceremony. Langara College.

In Potlatch as Pedagogy, Sara and Robert Davidson are in conversation on the ways in which the education system can be informed by traditional Haida governance. She explores a variety of concepts – those that have most impacted me are the principles of “Learning emerges through strong relationships,” “Learning occurs through contribution” and “Learning honours history and story.” In each of these sections she explores the ways these are true in the Haida feast system, discussing examples with her father (an acclaimed Haida artist and cultural revivalist), as well as examples from her experiences as an educator in the school system. Just as instructional practices can be informed by these principles, so too can social emotional support.

Mowatt, G (2024). Gwalxyee’enst: Love and Refusal as Felt Research with Gitxsan Youth [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Victoria.

In this doctoral thesis, Gitxsan scholar Gina Mowatt explores the concepts of healing, love, and refusal, in the contexts of arts based methodologies in an elementary school on Gitxsan territory. I felt challenged by some of the concepts around refusing trauma narratives and problematising healing as a requisite discrete and mandatory outcome for sovereignty amidst ongoing colonial violence. I come back to these seeming contradictions often, and it informs my thinking on education broadly, as well as wellness and healing oriented programming within the education system.

Williams, L. (2008). Lil’wat Principles of Learning (did you know) – strong nations. Lil’wat Principles of Learning (Did You Know) – Strong Nations. Retrieved October 8, 2021, from https://www.strongnations.com/gs/show.php?gs=4&gsd=3910.

The Lil’wat Principles of Learning were articulated by Dr. Wanosts’a7 Lorna Williams in a 2008 course at the University of Victoria regarding Indigenous pedagogies. Articulated within these principles is a series of concepts that educators benefit from considering with regards to creating affirming classrooms that promote both learning and overall wellbeing. Kat’il’a is a principle that particularly impacts my perspective on this – it is defined as seeking spaces of stillness and quiet amidst our busy lives. This is difficult in the education setting where we often feel pressured to fill space with what is seen as learning, however I believe it is an essential part of building a supportive environment for social emotional wellbeing. It is natural for humans to rest, just as it is natural for pretty much all plants and animals in nature to have periods of rest, and it is essential that we respect and honour that, as articulated in these principles.